Worms

It’s a hot day in early May and I’m poking through a tray of wet worm castings, otherwise known as worm poops, in a Plant and Soil Science lab at the University of Vermont. I’m looking for worm cocoons, mud-colored spheres about two to three millimeters in diameter, for Dr. Josef Görres, Associate Professor in the Department of Plant and Soil Science. Fingers muddy from crushed castings, I carefully squeeze a possible cocoon.

It is hard and round, but has a rubbery resilience between my fingers. We find six cocoons in a soil sample we collected earlier that day from a location near Shelburne Farms in southern Chittenden County, Vermont. Görres’ research focuses on soil quality and agriculture, but he’s become particularly interested in earthworms due to concerns about the negative affect they’re having on Northeastern forests.

Growing up, I spent a lot of time poking around the woods and never questioned finding earthworms under every rock. I was out of college before I learned that all earthworms in the Northeast came from Europe or Asia; the natives were wiped out by the last glacial period. Dr. Tim Fahey, a professor in the Department of Natural Resources at Cornell University, tells me it’s assumed that the first worm invaders tagged along with early European settlers some 300 years ago.

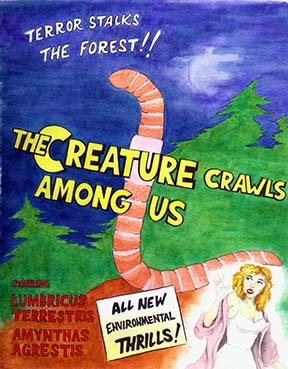

Of the more than two dozen non-native earthworms in New England, two species are especially interesting for those monitoring forest health. The most familiar is Lumbricus terrestris, better known as the nightcrawler, because these large worms come to the soil surface more often than other species. L. terrestris worms dig vertical burrows, but feed from the surface by pulling leaf litter down into their burrow. They cap their burrows with small piles of leaves and debris called middens. The other worm being closely watched is Amynthas agrestis, called the “crazy snake worm.” These worms live and feed in the leaf litter and do not make burrows. They are very active (for worms). When Görres shows me my first Amynthas, he places it on his palm and it twists and flips like it’s, well, crazy.

Lumbricus and Amynthas worms live and feed differently in the soil, but they have similar net effects. When they move into a forest, they eat away the thick duff layer (the top layers of decomposing leaf litter) while churning up the top soil horizons. According to Fahey, it takes several years to a decade for these changes to occur. The end result is a compacted surface soil horizon with little organic matter, below a layer of last year’s leaves. If Lumbricus worms are responsible, there will be middens scattered underneath the leaves. If Amynthas worms are responsible, there will be an extra layer of loose and crumbly worm castings up to four inches deep between the leaves and the actual soil surface.

In any forest, worm-induced changes to the soil structure can have far-reaching consequences. Without a good duff layer, trees have a harder time absorbing rain water. The rain instead washes away important nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus in the top soil, and the subsequent erosion exposes the roots of established trees.

It turns out that earthworms have good taste: they like maple leaves. The worms are less interested in coniferous leaf litter, although both Lumbricus and Amynthas worms have been recorded in woodlands with little deciduous leaf litter. Görres worries that maple forests could eventually shift because of worm-related environmental stresses to being dominated by trees the earthworms like less, such as conifers. While this remains speculation, it’s a troubling thought for anyone managing a sugarbush.

Earthworm activity also takes a toll on native understory plants. The loss of the duff layer, which acts as a seed bank for ephemerals, and the altered soil structure limits the potential for forest floor plants to germinate and survive. The worm-invaded sites I visited were all bare below the trees, allowing us to stroll along like we were walking through a park. Görres tells me these sites should have all required serious bushwhacking.

I did see many maple seedlings at the Shelburne Farms site, but without other understory plants to accompany them, Görres fears they take the brunt of deer browsing. Fahey adds it’s possible the worms themselves are eating enough of the seedlings’ roots to harm them. Studies have shown that worms can eat up to 20 percent of a mature sugar maple’s feeder roots. He doubts this is a problem for an established tree, but it could be too stressful for a seedling.

There’s also evidence that earthworms affect the amount of carbon a forest can sequester, something to consider as atmospheric carbon dioxide levels continue to rise. Fahey says that in one recent study, wormy forest soil contained about a third less carbon than worm-free forest soil.

So does all this mean that our forests are about to be overrun by alien destroyers?

Fahey sees the earthworm invasion as more of a limited occupation.

In the central New York forests that he’s been monitoring for 13 years, he hasn’t observed much advancement by the “earthworm front”. The European worms at his study sites are not marching steadily across the land to take over new habitats. Görres says that, on their own earthworms, even Amynthas, move only 10 meters in a year at best, but not uphill and only if they don’t like their current location. Görres’ opinion is that horticultural activities are primarily responsible for encouraging the spread of Amynthas and bait dumping by those out fishing spreads Lumbricus.

As for their current distribution, earthworms hang around the same places people do. Görres says forests above 2,500 feet are safe from worms. On Fahey’s hiking trips throughout the Northeast, he makes a point of checking for worms. He doesn’t find them along the ridge lines: they aren’t in the Berkshires, the White Mountains, or the Green Mountains. He does find them when the trails descend back toward civilization. Fahey attributes these observations to low soil fertility and reduced human activity in mountainous areas.

Görres and Fahey, working in different states, describe similar observations about earthworm activity. But they differ in their outlook on the future spread of worms, and the potential danger that these worms pose to forests. Where Görres interprets these observations as alarming indicators of the disruptive potential of invading earthworms on our northeast forests, Fahey is less concerned.

Görres sees Lumbricus and Amynthas earthworms as a major force of forest change in the Northeast, especially in maple forests, which have special cultural and economic value.

To Fahey, the situation is less dire because he doesn’t see the worms moving on their own, or very fast. The European worms at his study sites in New York have been there for over a century and he thinks they've already spread to the sites they prefer. He cites a field station in Michigan where scientists have been monitoring the spread of European earthworms for over 100 years and the worms are still most abundant where they were originally introduced. He acknowledges that the newcomer Amynthas worms are expanding into new habitats much more than the European species, but he sees worms in general as less of a threat to forests than deer, climate change, and exotic pathogens.

If you want to prevent earthworms from gaining a foothold in your forest, Görres has some suggestions: Only plant ornamentals with bare roots or check the potting soil thoroughly for worms, limit the worms’ food options by not using mulch and by raking up fallen leaves, and only use vermicompost from a trusted source. He’s skeptical about pesticide options.

As with many complex ecological questions, it’s hard to come to a definite conclusion about the Northeast’s invasive earthworms. There is enough evidence to say that they have the potential to profoundly alter the forests they adopt as home, if they haven’t already. Yet it is also possible that this invasion is already contained by the very nature of the invaders. Either way, the worms are here, and only time will tell just how they shape our forests. ![]()

A version of this article was published in the Northern Woodlands Magazine. Check out their website here: https://northernwoodlands.org/