Legumes in the Garden

Stroll through your garden and you might admire the progress of your peas and green beans, if you grow vegetables, or you might appreciate the showy purple spikes of lupines, if you prefer flowers. You might be shaded by an ornamental locust tree as you consider pulling weedy clovers and vetches out of your cultivated beds. While some of these plants are grown for food or for their beauty and some of them we'd rather not grow at all, they have something in common: they're legumes.

Legumes are a family of plants that have a symbiotic relationship with special soil bacteria, collectively called Rhizobium, that have the ability to fix nitrogen from the air, making it available to their plant host. Dr. Jeanne Harris, Associate Professor in Plant Biology, studies the symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes at the University of Vermont.

If you've ever fertilized your garden, you likely already know that plants need nitrogen to grow well. Nitrogen is a key component in proteins, which plants (and animals!) need. Nitrogen is actually all around us – 78% of the air we breath is composed of nitrogen gas. Unfortunately, when nitrogen is a gas it doesn't interact much with other chemicals. As Dr. Harris explains, that's where the Rhizobium come in.

Rhizobium bacteria have figured out how to pull nitrogen gas out of the air and convert it into nitrogen-containing ammonia. To put in perspective how impressive this is, the preferred industrial process that produces ammonia for agricultural fertilizers requires temperatures up to 930 F and 200 times atmospheric pressure. While Rhizobium don't need those kinds of temperatures and pressures, fixing nitrogen is, as Dr. Harris puts it, “horribly energetically expensive”.

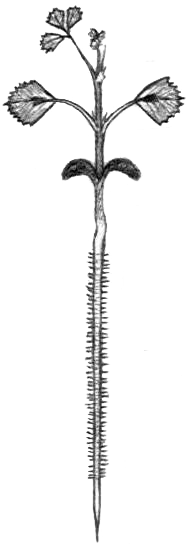

No wonder Rhizobium prefer to have a host plant to help them out. The basis of the symbiosis is simple: the Rhizobium provide nitrogen in the form of ammonia and the plant provides food and shelter in a unique root structure called a nodule.

Dr. Harris describes how legumes form root nodules as a chemical conversation between the Rhizobium and the plant. The plant releases flavenoids that the Rhizobium in the soil detect. The Rhizobium go into infectious mode, signaling back to the plant. The legume responds by forming a nodule for the Rhizobium to infect. This chemical conversation is important because each plant-Rhizobium partnership is unique: each type of Rhizobium bacteria needs to find the right plant partner.

If you've ever grown legumes and used an inoculant on them, the powder or liquid you used was a way to add the right Rhizobium to the soil around your plants, ensuring their roots would meet up with enough of the bacteria to form many nodules. Since each species of legume needs a different species of Rhizobium, each inoculum is different, so what works for your peas won't work for your soybeans.

This symbiosis has been very beneficial to legumes, since they essentially have their own fertilizer factory in their roots. “The ability to fix nitrogen has made legumes incredibly widespread”, Dr. Harris says. They appear across habitats from the tropics to New England in diverse forms from ground cover to trees.

The legume-Rhizobium symbiosis has also been beneficial to people. With nitrogen readily available, legumes make protein-rich seeds, like lentils and soy, that have been food staples for centuries. Legumes can also act as “green manure” in agriculture. When they die, the plants can be tilled into the ground and their extra nitrogen will enrich the soil.

Dr. Harris summed up with a final thought. While we see the above-ground community in our gardens every day – how the pollinators, herbivores, and other plants interact – we don't often think about the unseen, underground community of microorganisms that also connect with the world above. Even researchers are just beginning to think in terms of a soil microcommunity, and legumes and Rhizobium are suspected to be key players in that underground world. ![]()